In recent years, much attention has been given to China's treatment of ethnic minorities in regions like Tibet and Xinjiang. However, the situation in Southern Mongolia (officially known as Inner Mongolia) has often remained overlooked. A 2024 study by Zhao, Zhang, and Leibold sheds light on how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) uses media not just to inform, but to redefine reality—masking cultural repression under narratives of harmony and development.

The paper focuses on the role of the Inner Mongolia Daily (IMD), the official Party newspaper in the region, during the controversial bilingual education reforms of 2020. These reforms, which replaced Mongolian-language instruction with Mandarin in core subjects, sparked protests among ethnic Mongolians who recognised this as a direct threat to their cultural identity.

Rather than addressing public concerns, the CCP-controlled media launched a campaign to reframe the issue. Zhao et al. analyse over 100 articles published by IMD during this period and identify three dominant narratives used to manage public perception.

First, the media emphasised themes of gratitude and economic progress. Ethnic Mongolians were portrayed as beneficiaries of the CCP's policies—rescued from poverty and backwardness through Party leadership. This narrative framed compliance not as a sacrifice, but as a reasonable exchange for material prosperity.

Second, IMD promoted the image of Inner Mongolia as a model of ethnic unity and patriotism. Stories celebrated Mongolian citizens who displayed loyalty to the Chinese state, presenting assimilation as a virtue. Expressions of distinct Mongolian identity were only acceptable when aligned with CCP ideology.

Third, the study highlights the sinicisation of religion. Religious practices were reframed to conform with socialist values, stripping them of their unique cultural context. Faith, like language, was expected to serve the state.

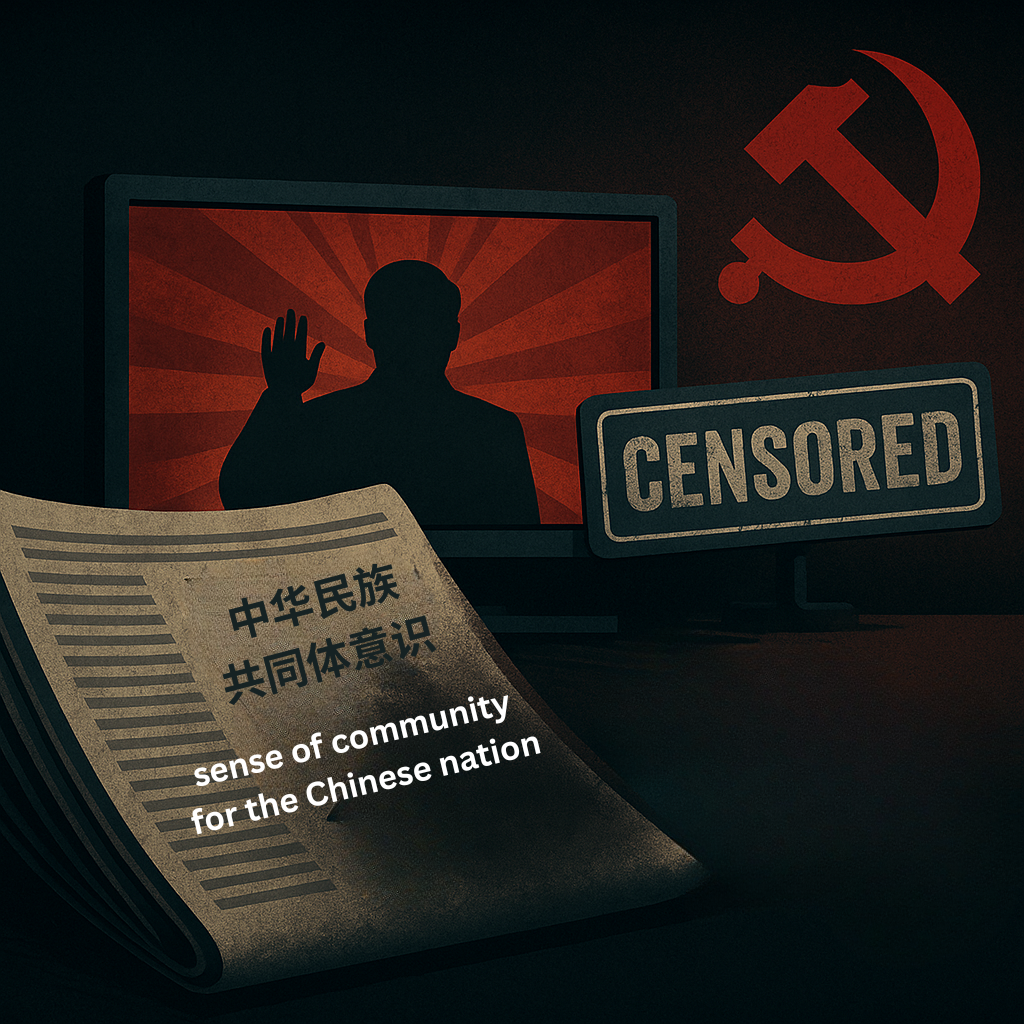

Zhao et al.'s analysis reveals that the CCP's media strategy is not merely about censorship or propaganda in the traditional sense. It is about reshaping narratives so thoroughly that acts of cultural erasure are presented as stories of progress, unity, and modernisation. Dissent disappears—not because it is violently suppressed (though that occurs too), but because it is written out of existence.

What makes this study particularly important is its demonstration of how ideological control works in quieter forms of repression. Unlike the more visible tactics employed in Tibet or Xinjiang, the situation in Southern Mongolia is managed through subtle manipulation of public discourse, making it harder for international observers to recognise the extent of the cultural harm being inflicted.

Zhao et al.’s analysis is more than just an academic exercise — it exposes a reality that many Southern Mongolians, including myself, have lived through but struggled to articulate on a global stage. While international attention often focuses on visible repression—mass arrests, surveillance states, internment camps—the quiet dismantling of a culture through controlled narratives is equally destructive.

The CCP’s strategy in Southern Mongolia is sophisticated. It doesn't rely solely on overt force but uses ideological warfare to convince both domestic and international audiences that cultural assimilation is "progress." This is what makes our struggle so difficult to communicate: when state media floods the world with images of smiling citizens and stories of development, the erasure of language, heritage, and identity becomes invisible to those not directly affected.

What struck me most from this study is how effective these propaganda tactics are in normalising oppression. By framing Mongolian identity as something to be "guided" by the Party, the CCP strips it of autonomy. Our language becomes a relic, our traditions reduced to folklore approved by the state, and any desire for cultural preservation is reframed as resistance to modernity.

This is why advocacy for Southern Mongolia must evolve. It is not enough to highlight isolated incidents of repression—we must expose the systematic narrative manipulation that enables this cultural genocide to continue unnoticed. The world must understand that repression in Southern Mongolia doesn’t always look like soldiers and prisons; it often looks like newspaper articles, school policies, and staged celebrations of "ethnic unity."

For me, Zhao et al.'s work reinforces the urgency of international solidarity. Southern Mongolians are fighting not only against policies that erase our culture but also against a global perception shaped by the CCP’s carefully constructed narratives. If we fail to challenge these narratives, we risk allowing history to record our assimilation as a voluntary path to prosperity — when in truth, it is the slow suffocation of a people’s identity.

Our resistance must therefore focus on reclaiming our story, amplifying voices that the CCP seeks to silence, and educating the world on the dangers of ideological repression disguised as harmony.

Zhao, Y., Zhang, S., & Leibold, J. (2024). Unravelling Narratives: Chinese Official Party Media’s Representation of Inner Mongolia Amid Reforms.

Keywords: Inner Mongolia, Southern Mongolia, Chinese propaganda, CCP media control, cultural genocide, Mongolian language repression, sinicisation, ethnic minorities in China, forced assimilation.